Best first paragraphs set up the masters’ novels

Hammett, Chandler, and Simenon with 3 great ways to start a book

If you have a lot of time to waste, you never judge a book by its cover. But don’t try telling me you don’t judge it by its first paragraph.

If you have a lot of time to waste, you never judge a book by its cover. But don’t try telling me you don’t judge it by its first paragraph.

What makes a great first paragraph? And which are the best novel first paragraphs? We all have favorites first paragraphs, some of which have become clichéd –– as happens to anything, whether it’s the best of times or the worst of times, or if you grew up in a family that was unhappy in its own way… See what I mean?

In general fiction it’s hard to beat Hemingway’s opening to The Sun Also Rises for laying out the narrator’s character, as well as the character being described: “Robert Cohn was once middleweight boxing champion of Princeton. Do not think that I am very much impressed with that as a boxing title, but it meant a lot to Cohn.”

But what about crime fiction? I’m going to look at Raymond Chandler, who started every novel with something very special, and Georges Simenon, who was a nasty enough man to write perfectly bitter downbeat prose from the very start of his books.

Best first paragraphs: Hammett

Let’s begin, though, with the man who in many ways beats them all: Dashiell Hammett.

Hammett springs the reader into the novel with the last line of the opening paragraph

I bet you think I’m going to write about The Maltese Falcon, which in the first paragraph describes detective Sam Spade as looking “rather pleasantly like a blond Satan.”

But I’m not.

We’re going to look at the opening of Red Harvest, Hammett’s first novel, in which the detective he calls only “the Continental Op” heads to a corrupt small town. It starts this way:

I first heard Personville called Poisonville by a red-haired mucker named Hickey Dewey in the Big Ship in Butte. He also called his shirt a shoit. I didn’t think anything of what he had done to the city’s name. Later I heard men who could manage their r’s give it the same pronunciation. I still didn’t see anything in it but the meaningless sort of humor that used to make richardsnary the thieves’ word for dictionary. A few years later I went to Personville and learned better.

Here we get the introduction to the Op and a lot of insight into him. We learn that he’s a man who has been drinking in a bar in Butte, which implies that he likes rough places and cheap alcohol. He knows the jokes thieves make and so we learn that the “men who could manage their r’s” were thieves too. We also get our introduction to Personville, which is after all to be a central character, as it were, in the book.

Here we get the introduction to the Op and a lot of insight into him. We learn that he’s a man who has been drinking in a bar in Butte, which implies that he likes rough places and cheap alcohol. He knows the jokes thieves make and so we learn that the “men who could manage their r’s” were thieves too. We also get our introduction to Personville, which is after all to be a central character, as it were, in the book.

Most important, perhaps, given that this was Hammett’s first full-length novel: We get the voice. The voice of Hammett and the Op. The worldly, experienced voice of a man who has mixed with criminals long enough to have heard repeated references to one small, corrupt town over the years. A man who, in the course of the book, will do criminal things for decent ends.

It also has that Hammett trademark: the kicker in the final sentence of the paragraph (note that the “blond Satan” does this for The Maltese Falcon.) If a writer’s trying to hook a reader into his book with this first paragraph –– on the basis that it’s as far as a casual browser will bother to read –– he has to view the opening paragraph the way a journalist views his lead.

In journalism the first paragraph of a news story has to include all the essentials, the who-what-when-where-how, because readers may glance at that paragraph and move on. Putting significant information further down is called “burying the lead.” In a similar way, a writer needs to make his opening paragraph carry all the qualities that he or she invests in the entire book. It must include information about the kind of book it is and where it might be going. But it must also give us a clever line that jumps our eye further into the book –– once you’ve read the second paragraph, you’ll probably figure you ought to buy it.

Best first paragraphs: Chandler

Chandler refines ‘the voice’ still further

I’m writing this in a plain office in the corner of a Jerusalem building that was described by the realtor as “exclusive,” though it doesn’t exclude despondent ultra-Orthodox Jews panhandling for cash, plumbers who break all the pipes you hadn’t called them to fix, or the cheerful lady who lets her dog pee in the elevator. There’s the hum of heavy traffic from the road below and a view across the valley of brake lights on a highway where no one ever seems to move. The air is clear enough up here that I usually only smell me, sweating through the desert heat, except when the garbage truck empties the trashcans and sends up a rotten fruit ripeness, or when the khamsin blows and I can smell the dirt on the hot wind. There’s a mosquito in here, but the bastard isn’t friendly enough to show himself. When he does, I’ll do what people in the Middle East do best. There are already spots of my blood across the whitewash where his mosquito brothers and sisters felt the thick side of my fist.

I’m writing this in a plain office in the corner of a Jerusalem building that was described by the realtor as “exclusive,” though it doesn’t exclude despondent ultra-Orthodox Jews panhandling for cash, plumbers who break all the pipes you hadn’t called them to fix, or the cheerful lady who lets her dog pee in the elevator. There’s the hum of heavy traffic from the road below and a view across the valley of brake lights on a highway where no one ever seems to move. The air is clear enough up here that I usually only smell me, sweating through the desert heat, except when the garbage truck empties the trashcans and sends up a rotten fruit ripeness, or when the khamsin blows and I can smell the dirt on the hot wind. There’s a mosquito in here, but the bastard isn’t friendly enough to show himself. When he does, I’ll do what people in the Middle East do best. There are already spots of my blood across the whitewash where his mosquito brothers and sisters felt the thick side of my fist.

If that sounds like a spoof, you surely know who I’m caricaturing. Raymond Chandler, the grumpy god of the gumshoe genre, claimed not to have much time for the idea of a classic in crime writing. In one of his essays, he wrote that contemporary writers who aimed for historical fiction, social vignette, or broad canvas would never surpass “Henry Esmond”, “Madame Bovary”, or “War and Peace”. Crime writers, on the other hand, would easily be able to devise a better mystery than the ones detailed in “The Hound of the Baskervilles” or “The Purloined Letter”. “It would be rather more difficult not to,” he wrote.

Still, Chandler proved himself wrong. Or rather he proved that he was right not to focus so much on the mystery element and, instead, to build a mysterious atmosphere and display a sardonic sense of humor. From the opening paragraph. This is how he starts a long 1950 short story called Red Wind:

There was a desert wind blowing that night. It was one of those hot dry Santa Anas that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands’ necks. Anything can happen. You can even get a full glass of beer at a cocktail lounge.

Like the opening paragraph of Hammett’s Red Harvest, this tells you a lot about the narrator and his lifestyle. The booze parties, and the sense of being gypped at the cocktail lounge.

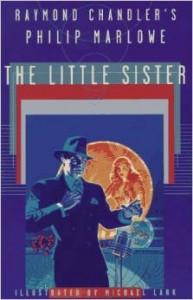

But the opening paragraph which might be said to define an entire genre –– and the sub-genres of attempts to copy the true representatives of the genre, and also to parody it –– starts Chandler’s 1949 novel The Little Sister:

The pebbled glass door panel is lettered in flaked black paint: “*Philip Marlowe…Investigations*.” It is a reasonably shabby door at the end of a reasonably shabby corridor in the sort of building that was new about the year the all-tile bathroom became the basis of civilization. The door is locked, but next to it is another door with the same legend which is not locked. Come on in –– there’s nobody in here but me and a big bluebottle fly. But not if you’re from Manhattan, Kansas.

That’s now a staple of the genre and, just as much, of its parodic/iconic avatar –– the detective innocently awaiting the moment when the lady arrives (or in this case, telephones) his shabby office. But what makes it so compelling is the voice of Marlowe, with its sense of regret at having become involved in the story and its unspoken acknowledgement of the inevitability of a repeat performance. After all, if Marlowe truly learned the lessons he claims to have taken on board, he wouldn’t be who he is. He’d be corrupted or cynical. Of course he’s neither.

That’s now a staple of the genre and, just as much, of its parodic/iconic avatar –– the detective innocently awaiting the moment when the lady arrives (or in this case, telephones) his shabby office. But what makes it so compelling is the voice of Marlowe, with its sense of regret at having become involved in the story and its unspoken acknowledgement of the inevitability of a repeat performance. After all, if Marlowe truly learned the lessons he claims to have taken on board, he wouldn’t be who he is. He’d be corrupted or cynical. Of course he’s neither.

It’s this subtext of honor (the knight in shining armor element of Marlowe’s character, Chandler called it) that elevates him above the many who copied him.

Best first paragraphs: Simenon

Simenon makes the detective confused and unsettles the reader

Georges Simenon wrote The Saint Fiacre Affair (known in English sometimes as Maigret Goes Home) in 1932. It’s one of the first of the 103 novels involved Inspector Jules Maigret. You can tell from books like this that the writer was a bit of a bastard. And we ought to be grateful for that.

Georges Simenon wrote The Saint Fiacre Affair (known in English sometimes as Maigret Goes Home) in 1932. It’s one of the first of the 103 novels involved Inspector Jules Maigret. You can tell from books like this that the writer was a bit of a bastard. And we ought to be grateful for that.

The opening of Saint Fiacre (I’m going to look at the opening half a page or so, rather than the opening paragraph, because the paragraphs are short, staccato, and make up what we might call a broken opening paragraph) is laden with the strangeness of waking in an unaccustomed place, and most of all the dismal return to a place whence one has fled. Here it is:

A timid scratching at the door; the sound of an object being put on the floor; a furtive voice:

“It’s half past five. The first bell for Mass has just been rung…”

Maigret raised himself on his elbows, making the mattress creak, and while he was looking in astonishment at the skylight cut in the sloping roof, the voice went on:

“Are you taking communion?”

All this is a re-creation of the small village atmosphere Maigret believed he had left behind him when he went to Paris as a young man to become a police officer. It’s a very meaningful atmosphere for me. For a couple of decades now, I’ve lived around the world as a journalist and writer. If I’d been an absolutely happy kid, I’d probably never have left. So whenever I go back for a visit, I become quiet, partially silenced by a bitter nostalgia and regret. Maybe that’s why I love this somber, atmospheric early episode featuring “le Commissaire” going back to his childhood village.

All this is a re-creation of the small village atmosphere Maigret believed he had left behind him when he went to Paris as a young man to become a police officer. It’s a very meaningful atmosphere for me. For a couple of decades now, I’ve lived around the world as a journalist and writer. If I’d been an absolutely happy kid, I’d probably never have left. So whenever I go back for a visit, I become quiet, partially silenced by a bitter nostalgia and regret. Maybe that’s why I love this somber, atmospheric early episode featuring “le Commissaire” going back to his childhood village.

Maigret appeared in so many movies and television adaptations — for Saint-Fiacre alone there are a 1959 French-language movie with Jean Gabin and two British TV versions — that it’s easy to think of him with the familiarity we often ascribe to endlessly reproduced cosy old-timers like Miss Marple and Sherlock Holmes. But Simenon had a lot more in common with his great U.S. crime-writing contemporaries. In Saint-Fiacre, he makes the lugubrious Chandler look like a breezy teenager skipping down a sunny small-town street in her bobby socks. Imagine that.

Simenon’s first editor wrote to him: “Your books aren’t real police novels. They aren’t scientific. They don’t play by the rules. There’s no love story in them. There’re no sympathetic characters. You won’t have a thousand readers.” Well, 550 million copies printed shows what that guy knew about potential sales. But he was right about the way the Belgian writer’s books worked. No real good guys and nothing — certainly not love — untainted by the grasping desire to escape a society of dying traditions and internal immigration.

The Saint-Fiacre Affair begins, then, with Maigret waking up in the inn of the village of Saint-Fiacre. At first he doesn’t recognize where he is. As it dawns upon him, he’s flooded with a heavy sense of darkness. He has returned to the village where he grew up to investigate a crime which is about to happen. (His office in the Paris police headquarters received a note saying that “A crime will be committed at the Saint-Fiacre Church during the first mass of the days of the dead.”)

As he strolls through the village, people glance at him curiously. They seem to recognize him, but can’t place the face of the son of the former steward at the local château, a face that left their community 35 years previously to pursue a career in the capital. All other traces of Maigret’s family are gone from the village and he wanders it sensing somehow that its very stones are unwelcoming.

As he strolls through the village, people glance at him curiously. They seem to recognize him, but can’t place the face of the son of the former steward at the local château, a face that left their community 35 years previously to pursue a career in the capital. All other traces of Maigret’s family are gone from the village and he wanders it sensing somehow that its very stones are unwelcoming.

When characters eventually recognize him or when he owns up to being from Saint-Fiacre, they seem to wonder what the hell could’ve brought him back. It’s clear they don’t trust him. There’s no hale slap on the back or curiosity about what he’s been doing all these years. Simenon captures the isolation and suspicion of the French peasant for the big city perfectly. What these people are signaling to Maigret — and what he instinctively realizes -– is that he may have been born in Saint-Fiacre, but the moment he left he ceased to belong to it. They owe him nothing. He’s on his own. That’s all communicated in that opening staccato sequence.

If you’ve ever been back to a place where you weren’t happy as a kid, a place from which you wanted to escape, you’ll feel as though you’re reading your diary, not a detective novel.

At the first mass, the Countess of Saint-Fiacre dies of a heart attack. With his crime delivered as promised, Maigret uncovers a clue at the scene and tracks the killer. But it’s really his own despondent sense of alienation that’s at the heart of this novel, and it’s there right from the first paragraph.

Write about trauma to relieve the emotion

Write about trauma to relieve the emotion