What do you do when you want to be writing dialogue that’s fresh?

Writing dialogue cheatsheet to find fresh angles on your characters

Posts with writing dialogue tips always say more or less the same things about grammar or writing dialogue for two characters as opposed to three characters. In this post I’m going to give you some alternative and unusual sources of inspiration for writing dialogue in fiction. First let’s recap on the tips you get everywhere else:

Posts with writing dialogue tips always say more or less the same things about grammar or writing dialogue for two characters as opposed to three characters. In this post I’m going to give you some alternative and unusual sources of inspiration for writing dialogue in fiction. First let’s recap on the tips you get everywhere else:

• Sometimes the characters should talk across each other (Bill: “What time is it?” Ben: “I hate that guy.”)

• Sometimes they shouldn’t answer each other (Bill: “What time is it?” Ben grimaced and put sugar in his coffee.)

• Don’t never go usin’ dialect nor accents fur yer speech, y’all

• Don’t explain within the dialogue (“Yes, and the reason I did that is all because…)

The rules in other posts on dialogue are usually negative, as you may have noticed. So let’s get positive.

1. Use the sample conversations in language textbooks

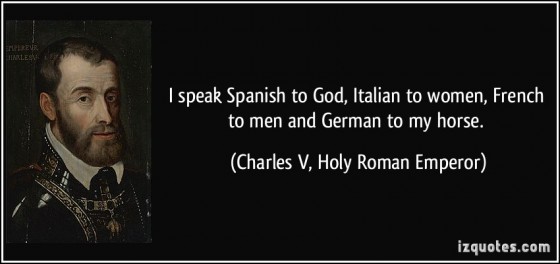

You can tell a great deal about people (or a people) from the conversations in language textbooks. After all, they aim to teach you the words people speak, but also the character of those people and what it might be like to live in their society.

Examining how this plays out in textbooks is a way to build your own skill with writing dialogue in a book, and not only with foreign characters.

I first cottoned to the fact that language lessons don’t only tell you which words to use when I learned Spanish. My textbook included a basic conversation between a woman and her boyfriend. It went like this:

I first cottoned to the fact that language lessons don’t only tell you which words to use when I learned Spanish. My textbook included a basic conversation between a woman and her boyfriend. It went like this:

Maria: I love you! Do you love me?

Pablo: What is love, anyway?

Maria: I hate you!

See? Passionate, fiery Latins.

Here’s another example of how I found language textbooks good for giving me a sense of place and people. My Hebrew textbook featured highly critical know-it-alls.

Avital: Do you like this actress?

Avi: I’m not crazy about her.

Avital: How is the ice-cream at this café?

Avi: It’s okay, but I know a better place for ice-cream.

Twenty years on and still living in Jerusalem, I have a more nuanced view of Israelis, but these conversations are still a good basic tool for understanding their sense of insecurity and accompanying need to assert themselves.

Even if you never learned a foreign language, imagine a textbook about the people who live in your town written for a foreigner learning the language there. What subjects would you choose for the conversations? What characteristic phrases would you throw in? What attitude, above all, would the people have toward each other? That’s really where dialogue comes from. You have to feel the attitude of the character.

2. Use traditional folk stories to get a window into culture and speech

Folk stories are another way to get ideas for attitude. Take the Palestinians. My first textbook of Levant Arabic featured conversations in which a fabled funny character named Jouha, known to be stupid, would end up being so stupid he came full circle and turned out to be cunning:

Folk stories are another way to get ideas for attitude. Take the Palestinians. My first textbook of Levant Arabic featured conversations in which a fabled funny character named Jouha, known to be stupid, would end up being so stupid he came full circle and turned out to be cunning:

Neighbor: Jouha, can I borrow your donkey?

Jouha: I don’t have a donkey.

(Donkey brays inside Jouha’s house.)

Neighbor: You do have a donkey. I can hear it.

Jouha: What’s this? You don’t believe me, but you believe my donkey?

3. Translate foreign phrases, rather than simply leaving them in italics

In my Omar Yussef novels, I try to capture the rhythms of Arabic speech. I also translate directly a number of very formal Arabic phrases, rather than simply putting them in a transliterated italics as is often done with snatches of foreign dialogue. I believe it gives the flavor of speech, and also a sense of how people relate to each other in a traditional society.

For example, there’s nothing poetic about “Good morning,” and what’d be the point of just italicizing “Sabah al-kheyr”? But try this translation: “Morning of joy.” To which you respond: “Morning of light.” Now that’s beautiful. And it’s what Palestinians say to each other every day.

When my Palestinian characters receive a cup of coffee—the ritual that accompanies every meeting in the Arab world—they say “May Allah bless your hands.” The person giving them the coffee responds, “Blessings.” Also very beautiful, but more than that a sign of respect and of acknowledgement.

There are, of course, Arabic phrases like this for so many situations and they often convey something beyond the basic meaning of the phrase. For example, in The Samaritan’s Secret, my third Omar Yussef novel, a character tells a priest “Long life to you.” Omar and all the other characters present understand immediately that this means someone has died. (The unspoken part of the phrase is, “…but eventually you’ll die like the guy whose death I’m going to tell you about.”)

There are, of course, Arabic phrases like this for so many situations and they often convey something beyond the basic meaning of the phrase. For example, in The Samaritan’s Secret, my third Omar Yussef novel, a character tells a priest “Long life to you.” Omar and all the other characters present understand immediately that this means someone has died. (The unspoken part of the phrase is, “…but eventually you’ll die like the guy whose death I’m going to tell you about.”)

How does this affect the plot or pacing of my books? Well, in some thrillers, a character can jump through a door and start berating everyone in sight, even beating them up. In Palestine, he has to—absolutely has to—wish them blessings from Allah and inquire after their health first.

If he didn’t, he’d be showing himself to be a really, really bad guy. And that would be giving away the ending.

4. Use local phrases and aphorisms

In my historical novels, I’ve used references to the culture of the day and aphorisms that’re current only in that particular language as a way of creating the kind of speech that rings true. I steer clear, of course, from archaisms, just as in any context I avoid dialect (because it comes across as comic, and in thrillers that isn’t what I’m after.)

Here’s a paragraph from A Name in Blood, my novel about the Italian artist Caravaggio. At this point Caravaggio is in Rome with some of his friends. It’s 1605. But I’m aiming to make them very contemporary in that they’re rough characters. I added some tone with an Italian phrase about getting up early that’s a parallel to the English early bird and his worm.

“The air of the early morning was clear, free of the foul odors that would rise from the littered ground in the day’s heat. Prospero blew a kiss at an old woman hauling a basket of figs towards the market in the Campo de’Fiori. ‘Who can be unhappy in Rome?’ The little man was missing a few teeth from tavern brawls. Those that remained shone through his ginger beard. ‘Well, late sleepers don’t catch any fish. I’m off, ragazzi.’ He shambled towards the Corso.”

5. Use the speeches and reported words of actual historical characters

Historical fiction also brings other advantages in writing dialogue––actual historical utterances of real characters. In The Ambassador, my thriller about Nazi Germany, I used speeches by Hitler and his actual words reported in the memoirs of those who were close to him to build his character. Here’s Hitler talking to his chief of security services, Reinhard Heydich, and I’ve used words taken verbatim from one of his reported rants:

Historical fiction also brings other advantages in writing dialogue––actual historical utterances of real characters. In The Ambassador, my thriller about Nazi Germany, I used speeches by Hitler and his actual words reported in the memoirs of those who were close to him to build his character. Here’s Hitler talking to his chief of security services, Reinhard Heydich, and I’ve used words taken verbatim from one of his reported rants:

“Hitler hesitated. Statistics were not his field. They threw him off. Heydrich blinked slowly, a silent signal for the Führer to go on.

In his head, Hitler entered a battle with the Jews. He firmed his lips. He was on the field, on the attack, resolute. “In removing the Jews, I eliminate in Germany the possibility of creating some sort of revolutionary core or nucleus. If our opponents are victorious in this struggle, the German people would be eradicated. Bolshevism would slaughter millions and millions and millions of our intellectuals. Anyone not dying through a shot in the neck would be deported. Children will be taken away and eliminated. This entire bestiality has been organized and planned by the Jews. Don’t expect anything else from me except the ruthless upholding of the national interest in the way which, in my view, will have the greatest effect and benefit for the German nation.”

‘You may count on me, my Führer.’”

6. Use historical documents and imagine them into actual speech

There’s another way to plumb history for dialogue and speech. In The Ambassador, I took the minutes of the Wannsee Conference (at which Heydrich first told government officials that the Jews were to be exterminated) and turned it into a dialogue.

Here’s a bit of the original minutes of the meeting, as taken down by Adolf Eichmann (you can read the whole thing here):

At the beginning of the discussion Chief of the Security Police and of the SD, SS-Obergruppenführer Heydrich, reported that the Reich Marshal had appointed him delegate for the preparations for the final solution of the Jewish question in Europe and pointed out that this discussion had been called for the purpose of clarifying fundamental questions. The wish of the Reich Marshal to have a draft sent to him concerning organizational, factual and material interests in relation to the final solution of the Jewish question in Europe makes necessary an initial common action of all central offices immediately concerned with these questions in order to bring their general activities into line. The Reichsführer-SS and the Chief of the German Police (Chief of the Security Police and the SD) was entrusted with the official central handling of the final solution of the Jewish question without regard to geographic borders. The Chief of the Security Police and the SD then gave a short report of the struggle which has been carried on thus far against this enemy, the essential points being the following:

a) the expulsion of the Jews from every sphere of life of the German people,

b) the expulsion of the Jews from the living space of the German people.

In carrying out these efforts, an increased and planned acceleration of the emigration of the Jews from Reich territory was started, as the only possible present solution.

By order of the Reich Marshal, a Reich Central Office for Jewish Emigration was set up in January 1939 and the Chief of the Security Police and SD was entrusted with the management. Its most important tasks were…

Pretty chilling, isn’t it. The challenge with this scene was to add a layer of menace to the character of Heydrich as he’s discussing these very issues.

Here’s how I used that section for dialogue in ‘The Ambassador’:

Here’s how I used that section for dialogue in ‘The Ambassador’:

They settled around the long table, fifteen men with Heydrich at the head and Eichmann keeping the official record of the discussion. Kritzinger found himself seated across from Heinrich Müller. The Gestapo chief stared at him, his brow angled downward, his eyes disapproving, mouth sullen. Kritzinger’s neck twitched and he focused on his papers.

Heydrich tapped his knuckles on the tabletop. “The Reichsführer-SS has appointed me delegate for the preparations of a final solution for the Jewish question in Europe. The Reichsführer wishes to have a draft sent to him concerning the organizational, factual and material interests in relation to this final solution. Therefore we have brought together in your persons the central offices immediately concerned. I shall begin with a brief report on the effort so far, inasmuch as it concerns the expulsion of Jews from every sphere of life, and from the living space of the German people.”

Kritzinger listened to Heydrich’s summary of the Jewish emigrations, the founding of Eichmann’s Central Office for Jewish Emigration, the extortion and bullying and fear—Heydrich called them “procedures”—used to speed the expulsion of the Jews. “All this was carried out in a legal manner,” Heydrich said.

Legal within a system of illegality, Kritzinger thought. He brought his hand to his mouth and his eyes flickered around the table as though he had spoken aloud. He shivered. What would he have done had Brückner not offered him a channel for his sense of disgust? Would he have sat here silently?

“In spite of the difficulties presented with emigration,” Heydrich went on, “such as the demand by various foreign governments for increasing sums of money to be presented by Jews at the time of their immigration, the lack of shipping space, increasing restrictions on entry permits, or the cancelling of such, 537,000 Jews have been sent out of the Reich between the assumption of power by the Party and October 31, 1941.”

Several of the men at the table turned briefly toward Eichmann. This was the work of his office. Though Kritzinger read jealousy and hatred on their faces, rather than congratulation, Eichmann gave a businesslike smile and bowed his head in acknowledgement.

“Another possible solution of the problem has now taken the place of emigration,” Heydrich said. “That is, the evacuation of the Jews to the East, provided that the Führer gives the appropriate approval in advance.”

Gestapo Müller made a whispering hiss like escaping gas.

I deliberately didn’t write this sequence in the point of view of Heydrich. I used the point of view of Kritzinger, one of the other functionaries who was at Wannsee. (Point of view, as you perhaps know, means that even when you write in the third person, you’re effectively seeing the scene through the eyes of a particular character.)

Heydrich knew what he was going to say, so his reaction to his own words wouldn’t be terribly revealing in this case. Kritzinger didn’t know what was coming. By using Kritzinger’s point of view I get to show his reaction to Heydrich’s words.

Crime fiction’s best first paragraphs

Crime fiction’s best first paragraphs