Empathy is vital for a writer

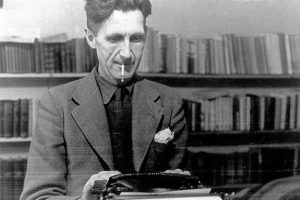

Malcolm Muggeridge (an old English literateur) once said that George Orwell “was no good as a novelist, because he didn’t have the interest in character.” Well, I didn’t need to tell you who George Orwell was, so you may doubt the judgment of the largely forgotten Muggeridge. But I think he struck at an important factor for novelist to remember.

Here’s why: Character creates empathy in a novel. It puts the reader in a relationship with the work. Muggeridge’s point was that politics were more interesting to Orwell than the people on whom he hung them. In “1984” we feel for Winston Smith because we imagine what it’d be like to be him – but we don’t really care that much for him as a character. In other words, if Orwell hadn’t had such a fabulous idea behind that novel, it would’ve failed because Winston was too much of an everyman.

Empathy in writing is the heart of the character test

Nonetheless, so much contemporary fiction fails the character test. Read the short stories in The New Yorker – which are fairly representative of today’s “literary” fiction – and you’ll generally see an authorial voice greatly distanced from the emotions of the characters. You’re not in a relationship with the characters, and you wouldn’t want to be in a relationship with the smart-ass authorial voice.

The same is true on the other side of the Atlantic. Ian McEwan’s distance and restraint makes me feel…distant and restrained. Which isn’t why I read a novel.

Superior smart-ass brings no empathy in writing

Instead of putting you in a relationship with the characters, writers like McEwan effectively put you across the dinner-party table from them. And they do it in the voice of an uptight, superior bore. How would you like to be stuck at a dinner party long enough to hear an entire novel read by such a voice? …Yeah, I didn’t think so.

So now we’re agreed (write a comment at the end of this post if we’re not agreed, and I’ll write back in a superior smart-ass voice, just to show you that I’m right) that empathy is what counts. Without it, your characters will be one-dimensional, no matter how good a stylist you are. But what’s the best way to learn about it?

How to put empathy into your writing

Some people are born with the ability to empathize. Others develop it. To a great extent I had to develop it. It’s a harder quality to build than you might think.

So if you’re not born with it, how do you get it?

Answer: go and live somewhere you don’t belong.

When you’re supposed to share the culture and attitudes of the people around you, you’re also expected to empathize without thinking about it.

You’re Welsh, I’m Welsh, thus without thinking about it we share perspectives and background which we don’t need to discuss. If you do discuss it, people will find you odd or boring. Certainly they won’t be able to explain themselves, because they too will feel like they’re talking about their culture in terms that’re too basic. Many of the questions you ought to ask will seem so obvious you won’t even think to address them.

Outsider listens, listener empathizes

As an outsider, you aren’t limited in that way. In fact, you’ll be forced to discuss and examine aspects of the culture around you which don’t make sense. The locals will explain themselves to you in a way that may begin at basic facts but will soon progress into how they FEEL about their culture and the people around them. Then you’ll be inside their heads. You’ll be able to empathize and build characters in your fiction.

For me, the place was for a long time Jerusalem. Over 20 years, I lived there not as an Israeli or a Palestinian but as an observer. In Jerusalem, were you to look at the behavior of the locals, they’d drive you crazy, unless you were able to observe them with a deep feeling for their emotions and experiences. That’s the empathy I mean, and it was one of the most important factors in my Palestinian crime novels.

Internationalizing empathy

I’m still giving myself that same challenge. I live in Europe now. My new book The Damascus Threat is a thriller set in Syria and New York–both places where I’ve either lived or spent a good deal of time. But the one I’m completing now (it’ll be published in a year) is set in New York, Luxembourg, Cologne, Frankfurt, Prague, Vienna, and Majorca. In this case, I found that by placing my characters in alien locations I forced them to show themselves to me.

Does that sound odd? Think about it. I did to them what I had done to myself for many years–and continued to do. I took them to places where they wouldn’t be able to fall back on old habits or easy knowledge. That showed them to me–and I hope to readers–in a way that’s more human and emotional.

So you don’t have to live somewhere else after all. You just have to make your characters go there.

My voice and his voice: first- or third-person narrative in the novel

My voice and his voice: first- or third-person narrative in the novel

Hi. Nice, interesting post, and a little as they are. I learned something totally new today!

Thanks, Nicolas. Glad you enjoyed.

‘Characters in alien locations’ — that’s why The Passenger is my favourite movie. Characters who wouldn’t otherwise meet thrown together on whatever pretext is good too, I think.

Hey, Matt, your comment in parentheses about leaving a comment was so weird because I could hear you saying that — a rare lapse in your writer’s voice. The consistency and tone of said ‘writer’s voice’ is, I think, one of the strengths of your fiction and nonfiction. From what you say of the smart-ass writers in the New Yorker, they sound too narcissistic to develop a voice beyond that which they use at dinner parties. Looking forward to reading The Damascus Threat.

Surely it’s the final 7 minute tracking shot that makes The Passenger so great…(That’s my smartass response.) Glad you “heard” me. Speaking out of a blog is a little like speaking from beyond the grave: it doesn’t happen often, but perhaps it’s all the more of a connection for that… I must watch some more Antonioni, now that you’ve mentioned him. Mrs Rees will only have you to blame, David.