Writing the truth by turning to fiction, instead of journalism

Journalism is fiction. Don’t believe me? Open a newsmagazine and you’ll be expected to believe that a given Hollywood star is actually a nice man, that you can drive everywhere and not get fat provided you lay off fruit, and that the latest development in the Middle East gives hope that things there will get better: well, of course, he isn’t, you can’t, and it won’t.

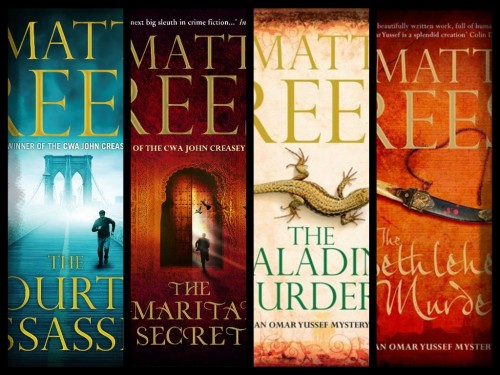

That is to say, it’s fiction. We don’t necessarily think of it as fiction, because fiction’s supposed to be interesting, and that’s more than can be said for most journalism. The difference between journalism and fiction is not quite what you’d expect. Why did I turn from journalism (and its inherent fictionalizing of reality to fit it into a newsman’s formula) to a realistic fiction with my Palestine Quartet about Omar Yussef, the first Palestinian sleuth in fiction?

Because I wanted to write the truth.

My experience as a journalist taught me that there are serious limits on what a journalist can convey to his readers. That’s somewhat because of libel laws. It’s also because a journalist has to counter the expectations of his editors, trying to bring them along with him to reach the same conclusions and then watching to see that someone else’s ideas don’t overtake the story during the editing process.

But mostly it’s because journalism even at its most worthy skirts around the essence of man. It was only rarely during a decade as a foreign correspondent that I was able to write about what happens inside the head of a Palestinian. Mainly I had to say what the latest incident of bloodshed meant for the “peace process,” even when there had clearly ceased to be peace and such process as remained was entirely orchestrated for politicians to play to their domestic supporters.

Journalism is a way to find people. Fiction is a way to understand them

Journalism took me to places I’d otherwise never have visited, or even known existed. It gave me an understanding of people I’d never have known and at the same time let me understand myself far more deeply than I would have done had I not met them, had I stayed at home in the world to which I was born.

I felt I knew something of what happened inside at least some of those Palestinians’ heads, the ones I knew best and in some cases liked best. I realized virtually no one would have understood this from most of what I wrote as a journalist, and I thought that was a shame.

I could have written journalism from the Middle East for another decade and at the end I’d have been able to say that usually I conveyed to readers the ugly surface of events here and that sometimes I’d been maneuvered by some editor into giving a bureaucratic summation of diplomacy which was patently worthless. My own understanding would have continued to grow, but except for my wife, who doesn’t get a chance to edit me over the dinner table, no one would know that. I thought that would be a shame. Particularly for my wife.

I wrote the Omar Yussef novels with a sense of liberation. Not liberation from the truth. Rather it was a freedom from the strictures of journalism. I found the best way to tell the truth. Not everyone can see the places I saw and meet the people I met as a journalist. But now at least they can read about them in my novels.

Hammett’s writing evokes emotion through reality

Hammett’s writing evokes emotion through reality