My historical thriller ‘Mozart’s Last Aria’ grew from an idea I had in the place where the great composer’s sister lived

Photo: The house in the mountain village of St. Gilgen where Nannerl lived

In 2003 I took a break from covering the violence of the Palestinian intifada to travel to Austria and the Czech Republic with my wife. I had seen some terrible things and lived through some dangerous moments. I wanted to experience some calm in the mountains, see some beautiful cities, and hear lovely music. I found all those things, but I also stumbled across something that made me come to life creatively. The trip became an impromptu Mozart tour. We happened to pass through the tiny village in the mountains near Salzburg where Mozart’s sister lived as the wife of a boring local functionary (and where by chance his mother had been born). I started to think about Wolfgang’s sister Nannerl, who had been almost as talented as him, cooped up in the mountains while her brother was famous in Vienna. As a writer of crime fiction, of course, I also started to think about her response to his death. Later, I was having dinner with Maestro Zubin Mehta, formerly the musical director of the New York Philharmonic and now holder of many top positions in the world of classical music. I asked him which of all the great composers he valued most highly. “I’d find it hard to live without Mozart,” he said. That started me thinking about those people who had lived with Mozart. After his death at only 35, what had it been like to live without him. To have lost one of the greatest geniuses in the history of the world. Over the course of many research trips to Vienna, I came up with the idea of posing Maestro Mehta’s question through Mozart’s sister. A musical prodigy who’s forgotten to history except as a footnote in stories about her famous brother, she knew him better than anyone. What might’ve been her response to losing him?

Why I wrote Mozart’s Last Aria as a historical crime novel

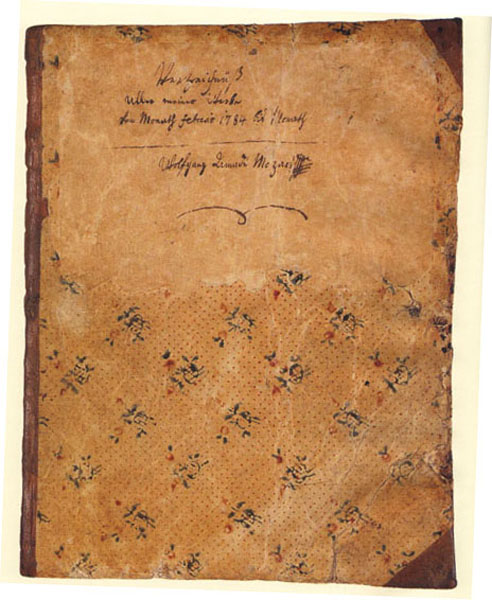

Photo: The cover of the catalogue in which Mozart recorded the titles of each of his compositions

I wanted to make the novel fit the music of Mozart. Not only in the way I described Nannerl and others performing his music. But in the very structure of the book. I decided to think of the novel in terms of one of Wolfgang’s piano sonatas. These are among my favorite pieces by the maestro. I chose one of his most disturbing sonatas, the A minor (known by its number designation K 310). Many people think of Mozart as a purveyor of happy little tunes compared to the sweeping emotionalism of Beethoven. But this sonata alone demonstrates the depths of emotion in Wolfgang’s music. He wrote it when alone in Paris after his mother’s death there. How does it fit the format of a crime novel? It begins with an Allegro maestoso that is deeply disturbing and almost discordant. Listen and you’ll see what I mean. I have Nannerl play this movement in MOZART’S LAST ARIA after she hears of Wolfgang’s death. I thought of this as the introductory theme of Act I of my novel, in which the calm world around Nannerl collapses with news of her brother’s death, when she resolves to find out what happened to him. The thoughtful second movement (Andante cantabile con espressione) is Act II of the book, where Nannerl slowly explores the Vienna Wolfgang left behind, including the delicate relationship with his wife, the fears of his friends and the dangers she senses. Act III is the final Presto movement, in which the disturbing themes of the first movement are resolved in a series of climactic scenes. It also represents the discovery of musical clues slipped into the first movement, just as Nannerl uncovers the truth over the last couple of chapters of the book. This idea gave me an emotional framework for the plot. Given that the A minor sonata was written in response to a death – that of Wolfgang’s mother – and that I wanted to explore Nannerl’s feelings about her dead brother, it seemed natural that I ought to make this a crime novel.

The Mozart Family

Leopold Mozart took his wife, Maria Anna, and his two surviving children, Wolfgang and Maria Anna (known as Nannerl, Little Nanna) on tour throughout Europe. (They had a number of other children who died as babies.) In an age when most people went no more than a few miles from home, the travels drew the family very close. Here the family is at the piano before a portrait of Anna Maria, who died when she traveled with Wolfgang to Paris in 1778. Leopold was born in 1719 in Augsburg and made his living as a court musician to the Prince Archbishop of Salzburg. He wrote a widely read instructional manual for the violin. He married Maria Anna in 1747, when she was 26. Though Leopold has often been portrayed as a small-minded control freak, he was a cultured man with a broad knowledge of literature and the sciences. After 1785, he seems to have become rather estranged from his son. Though he was 66, he took Nannerl’s baby son Leopold to live with him – far away from the mother — with the intention, apparently, of making a musical prodigy of him. But the old man died in 1787.

Nannerl

Born in Salzburg in 1751 at the end of July, Nannerl was a child prodigy at the keyboard, but her brother Wolfgang soon outshone her and took all the attention at concerts – and the attention of their father, who decided that the boy would be the one to carry the family’s fortunes. When that change became clear, Nannerl often collapsed into emotional fits and despair which left her in bed sometimes for weeks. She kept a diary in which she listed many of the social engagements that occupied her in Salzburg, as well as the pieces she continued to play at the piano. Though she was rather old for marriage and frequently feared she’d become an old maid, Leopold arranged for her to wed a dull provincial bureaucrat and consigned her to life in a remote mountain village in 1784. She bore three children, two girls who died at less than one and at 16, and a boy who outlived her by only 11 years. After Wolfgang’s death, she contributed to early biographers with stories of their childhood travels. When her husband died she returned to Salzburg, where she taught piano and died in 1829.

Wolfgang’s Wife

Mozart’s wife Constanze was born into the talented Weber family in 1762 in Mannheim (One of her sisters sang the role of Queen of the Night in the premiere of “The Magic Flute”). Wolfgang was initially in love with her sister Aloysia. When spurned, he improvised a song before the family: “Whoever doesn’t love me can kiss my ass.” (In later letters, however, he told Constanze she had “a kissable ass.”) After the Webers came to live in Vienna, Mozart became the family’s lodger. He married Constanze in 1782, against the wishes of father Leopold. An accomplished soprano, Constanze sang in Wolfgang’s C Minor Mass, performing at St. Peter’s in Salzburg when the married couple visited Leopold and Nannerl in Salzburg. The visit was pretty frosty. After Wolfgang died, she married a Danish diplomat and settled in Salzburg. She finished the biography of Mozart started by her husband and published it in 1828. She died in 1842.

Wolfgang and Constanze had two sons who survived infancy. (They lost four others as babies.) Karl Thomas Mozart was born in 1784. He settled in Milan where he abandoned music to become a civil servant. He died in 1858. Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart (in this portrait) was born a few months before his famous father’s death. He performed as a child in concerts memorializing his father and studied under various composers, including Salieri. Some of his piano compositions were quite popular in the early nineteenth century. He lived in Poland much of his life, carrying out concert tours and falling in love with an older Polish woman. He performed his father’s Requiem in Salzburg for Constanze’s second husband, not long before Nannerl’s death. Franz Xaver died in 1844.

7 novels to improve your thriller writing

7 novels to improve your thriller writing